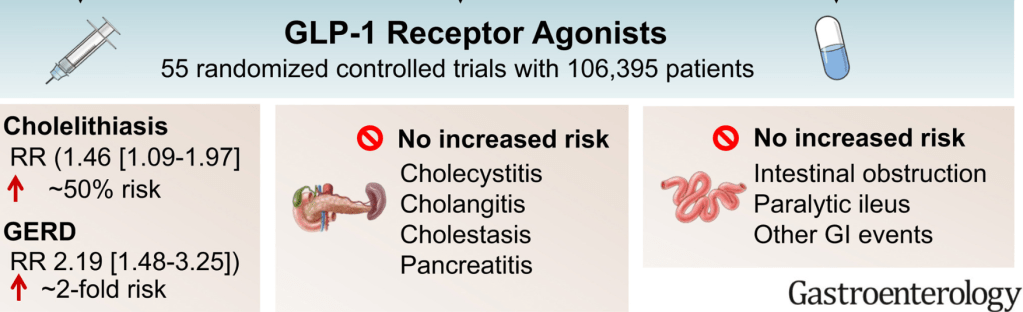

C-H Chiang et al. Gastroenterol 2025; 169: 1268-1281. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

With the widespread adoption of GLP-1 RAs, there have been increasing reports of adverse effects. This systematic review/meta-analysis (with 55 randomized controlled trials involving 106,395 participants) more fully describes the likelihood of GI adverse events.

Key findings:

- GLP-1RAs increased the risk of cholelithiasis (risk ratio [RR], 1.46; 95% CI, 1.09–1.97; 2 more cases per 1000) and probably increased the risk of GERD (RR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.48–3.25; 4 more cases per 1000) compared with placebo

- GLP-1RAs probably have little or no effect on the risk of other gastrointestinal or biliary events

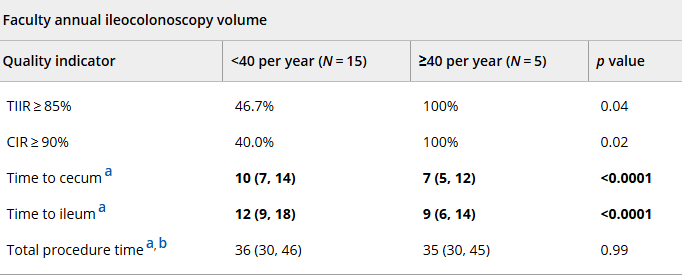

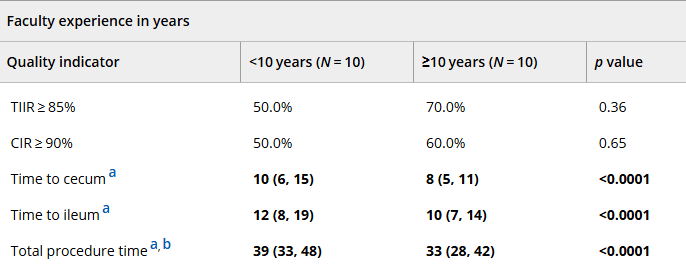

Figures 2 & 3 use a Forest plot to look at a large number of potential adverse gastrointestinal/biliary events. For example, cholecystitis and cholangitis had increased RR at 1.17 and 1.54 respectively. However neither reached statistical significance.

My take: GLP-1 RAs definitely cause adverse gastrointestinal effects, especially nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloating and reduced appetite. More severe adverse effects are quite uncommon and are unlikely to influence the decision to use these medications.

Related blog posts: