A recent Nutrition Pearls with one of our nutritionists, Baily Koch, as a moderator was very good: Christy Figueredo – Navigating GLP-1 Use in Pediatrics (episode 33, 58 minutes)

A Faccisorusso et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025; 23: 715-725. Open access! Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: A Meta-Analysis

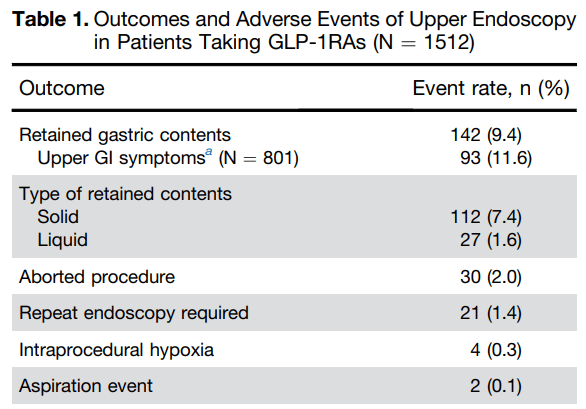

This is one of three articles discussing the issue of GLP-1RAs and potential complications with upper endoscopy. Faccisourruso et al performed a meta-analysis that included 13 studies (of 177 studies) involving a total of 84,065 patients.

Key findings:

- Patients receiving GLP-1RA therapy exhibited significantly higher rates of retained gastric contents (RGC) (OR, 5.56)

- Rates of aborted and repeated procedures were higher in the GLP-1RA user group. The absolute risk of aborted procedure was 1% in GLP-1RA users compared to 0.3% in non-users. The absolute risk of a repeated procedure was 2% vs 1% respectively.

- No significant differences were found in AE and aspiration rates between the 2 groups (OR, 4.04 and OR, 1.75 respectively). The absolute risk of aspiration was 0.3% in GLP1-RA users compared to 0.2% in non-GLP1-RA group

- Adverse events were higher in GLP-1RA users (0.3%) compared to non-users (0.1%)

In their discussion, the authors note that an “individualized approach based on the indication of GLP-1RA use (withholding the drug in patients with diabetes could lead to more harm)…a potential stragegy could be to place patients on a liquid diet the day before endoscopy, thus prolonging the duration of fasting for solid for at least 12 hours.”

The related articles:

- TS Barlowe et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025; 23: 739-747. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Do Not Increase Aspiration During Upper Endoscopy in Patients With Diabetes. Using administrative database claims, the authors found that GLP1-RAs, compared with DPP4i (dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors), had lower crude relative risks of aspiration (0.67), and aspiration pneumonia (0.95).

- SA Firkins et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025; 23: 872-873. Open Access! Clinical Outcomes and Safety of Upper Endoscopy While on Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Key findings:

My take: The totality of these studies confirms the increased risk of retained gastric contents in patients receiving GLP-1RAs. This in turn increases the need to abort/reschedule cases and may result in very a low increased risk of aspiration. To mitigate this risk, it may be sufficient to implement a liquid diet the day before endoscopy (avoiding solid foods for at least 12 hours prior to endoscopy). This is in agreement with the recent AGA Rapid Clinical Practice Update (see post below).

Related article on utility of GLP-1RAs: David Kessler, NY Times 5/7/25: In a World of Addictive Foods, We Need GLP-1s

“Like millions of others, I was caught between what the food industry has done to make the American diet unhealthy and addictive and what my metabolism could accommodate.

We may now be at the brink of reclaiming our health. New and highly effective anti-obesity medications known as GLP-1s have revolutionized our understanding of weight loss and of obesity itself. These drugs alone are not a panacea for the obesity crisis that has engulfed the nation, and we should not mistake them for one. But their effectiveness underscores the fact that being overweight or obese was never the result of a lack of willpower…

GLP-1s are revolutionary drugs that can drastically reduce caloric intake and improve health in a way I didn’t expect I would ever see. Now we need to complete that revolution by taking on the food industry and its engineered foods that are contributing to some of the most harmful health issues America faces today.”

Related blog posts:

- AGA Guidance: GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prior to Endoscopy includes the reference and summary of this article: Hashash, Jana G. et al. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Volume 22, Issue 4, 705 – 707. AGA Rapid Clinical Practice Update on the Management of Patients Taking GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prior to Endoscopy: Communication

- Getting over the Stigma of Medicines for Anxiety/Depression and Obesity

- Weight Gain If Semaglutide Stopped

- Semaglutide in Adolescent Obesity

- Fatty Liver Disease AASLD Practice Guidance 2023

- Meds for Obesity: AAP Guidelines

- Bariatric Surgery Declines as GLP-1 Medications Rise

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.