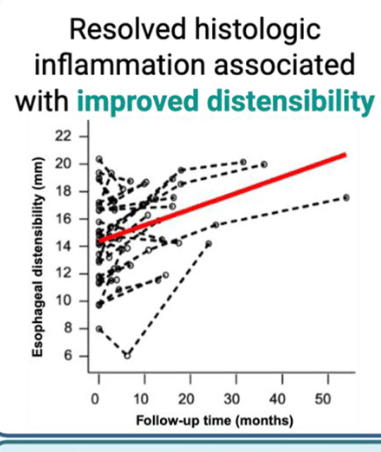

KV Kennedy et al. Gastroenterol 2026; 170: 287-297. Histologic Response Is Associated With Improved Esophageal Distensibility and Symptom Burden in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Methods: This was a prospective study with 300 endoscopies involving 112 patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).

Key findings:

- “Participants exhibiting a histologic response to treatment showed the most significant improvement in distensibility over time (1.41 vs 0.16–0.53 mm/y; P = .003).”

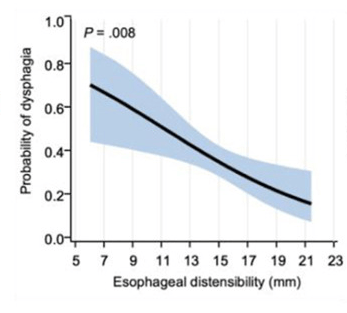

- “After adjusting for Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score and age at symptom onset, lower esophageal distensibility was independently associated with increased odds of patient-reported dysphagia” (odds ratio, 0.85; P = .008).

- “Baseline distensibility predicted the need for future stricture dilation (area under the curve, 0.757; P = .0003).”

- At baseline, fibrostenotic features were noted in 26 (23%) and strictures in 16 (14%).

Discussion Points:

- “Our results support the potential plasticity of esophageal remodeling based on the observed improvement in distensibility among patients with adequately controlled inflammation.”

- “A recent cohort study of 105 adult patients with EoE with more than 10 years of pediatric followup…found that patients with longer periods of histologic control were less likely to develop esophageal strictures.”

My take: The esophagus works better when eosinophilic inflammation is treated.

Related blog posts:

- Is Topical Budesonide Less Effective in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Strictures?

- FLIP Patterns for Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Practical Tips for Eosinophilic Esophagitis (Glenn Furuta,MD)

- Injecting Steroids for esophageal strictures -Does it work?

- Frequency of Strictures in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Mechanical Dilation vs. Medical Therapy for Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Eat More Chicken? (for EoE)

- EndoFlip Findings in EoE

- Briefly Noted: Esophageal Stricture Dilatations

- Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis with Budesonide

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Once vs Twice Daily Steroid Treatment

- Impact of Disease Severity on Eosinophilic Esophagitis Treatment Responses

- ACG 2025 Guidelines for Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- “Tug” Sign For Eosinophilic Esophagitis and EoE Bowel Sounds Tips

- Budesonide for Maintaining EoE Remission

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Prevalence and Costs in the U.S.