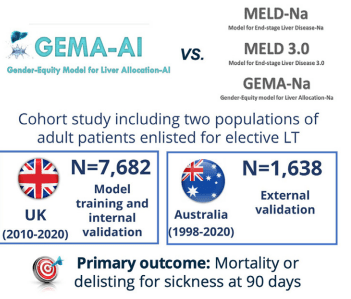

AM Gomez-Orellana et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025; 23: 2187-2196. Open Access! Gender-Equity Model for Liver Allocation Using Artificial Intelligence (GEMA-AI) for Waiting List Liver Transplant Prioritization

Background: “The current gold standard for ranking patients in the waiting list according to their mortality risk is the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease corrected by serum sodium (MELD-Na), which combines 4 serum analytic and objective parameters, namely bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR), creatinine, and sodium…2“

“The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) 3.0 was developed and internally validated in the United States,4 and the gender-equity model for liver allocation corrected by serum sodium (GEMA-Na) was trained and internally validated in the United Kingdom and externally validated in Australia.5… GEMA-Na was associated with a more pronounced discrimination benefit than MELD 3.0, probably owing to the replacement of serum creatinine with the Royal Free Hospital cirrhosis glomerular filtration rate (RFH-GFR)6 in the formula.5“

Methods:

Key findings:

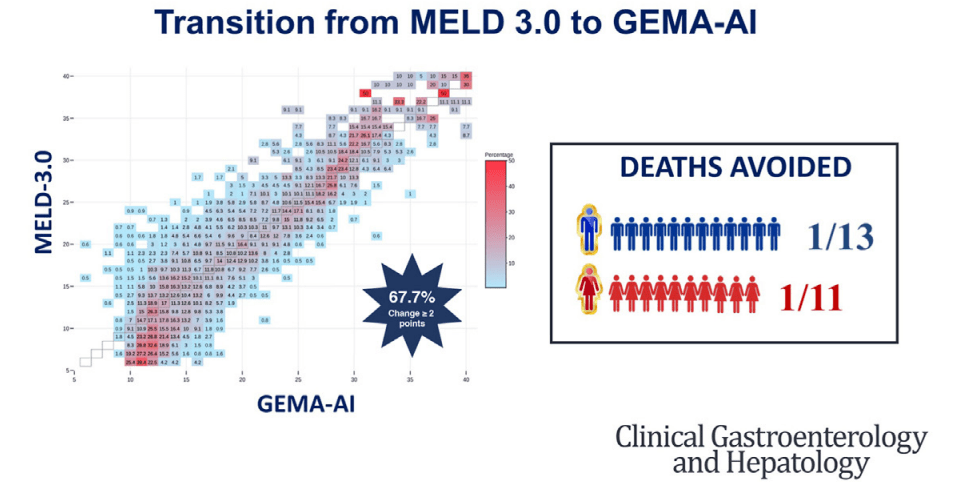

- GEMA-AI made more accurate predictions of waiting list outcomes than the currently available models, and could alleviate gender disparities for accessing LT

Discussion Points:

- The components of the current scores available for waiting list prioritization provide objective and reproducible information…which in turn are associated with the probability of mortality or clinical deterioration resulting in transplant unsuitability.18 However, this relationship is nonlinear…at a certain point, for the highest values typically found in the sickest patients, the relationship with the outcome risk becomes exponential.5 …GEMA-AI was the only adequately calibrated model and showed the greatest advantage on discrimination”

- An “advantage of nonlinear methodologies, and particularly of ANNs [artificial neural network], is their ability to identify patterns of combinations of values that are associated with an increased risk of death or delisting due to clinical worsening. While linear models give a fixed weight to each variable irrespective of its value or the value of other variables in the model, ANNs could capture specific combinations to modulate the weighting.19“

My take: In the movie, iRobot, Detective Spooner instructs the robot: “Sonny, save Calvin.” While things worked out in the movie, it turns out that the robot would usually make a better decision. This study shows that AI has the potential to reduce waiting list mortality by taking advantage of weighing non-linear variables.

Related blog posts:

- AI for GI

- The Future of Medicine: AI’s Role vs Human Judgment

- Artificial Intelligence in the Endoscopy Suite

- ChatGPT4 Outperforms GI Docs for Postcolonoscopy Surveillance Advice

- Will Future Pathology Reports Include Likely Therapeutic Recommendations?

- Medical Diagnostic Errors

- Answering Patient Questions: AI Does Better Than Doctors

- Dr. Sana Syed: AI Advancements in Pediatric Gastroenterology