T Shah et al. JPGN Reports 2026;1–5. Responsible laboratory surveillance of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease on biologic infusion therapy

This retrospective single-center study with 34 pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease examined the laboratory costs (2020-2021) associated with monitoring biologic therapy.

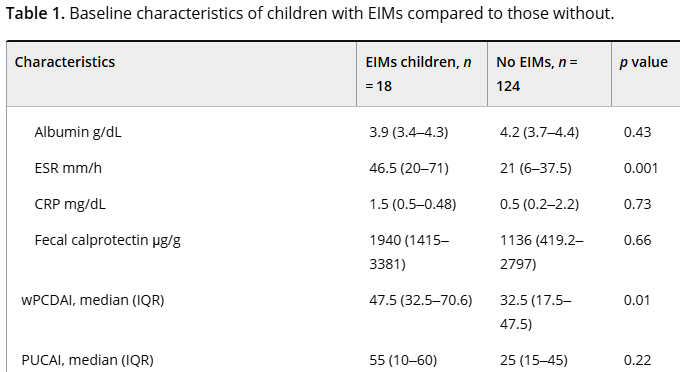

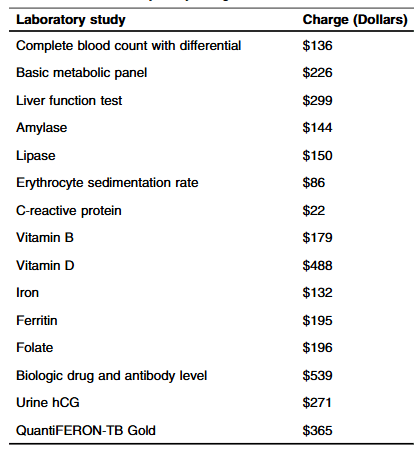

Methods: “Routine laboratory studies were defined as those part of the standardized infusion protocol at SBCH and were obtained with each scheduled infusion. The following laboratory studies were considered routine/standard: complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, vitamin D, iron, ferritin, vitamin B12, folate, urine hCG (if a subject was female). Other laboratory studies that were collected, but not considered routine studies included QuantiFERON-TB, and biologic drug and antibody level.”

Key findings:

- The average hospital charge for studies obtained per infusion was $1308.36 with an average annual cost of $9543.44 per patient

- Fifteen (6%) instances of change in clinical management were found. “Only a limited subset of the 15 laboratory studies included were utilized in making changes: biologic drug, Vitamin D, and iron level”

- During the study, 248 infusions were administered with a “total annual charge amongst all patients in the study was $324,447”

Discussion:

- “Our study population had well controlled disease as evident by low PCDAI and PUCAI scores…Our observations suggest the utility of routine laboratory surveillance at each biologic infusion is minimal, favoring decreased testing for IBD patients, especially those in clinical remission.”

- “We propose obtaining laboratory tests twice a year, or with every third infusion, for patients with mild disease or in remission based on their disease activity index scores. In our small cohort of patients, this change in practice would reduce the total annual costs by 66% ($214,154.82)”

My take: It has been my practice, for most patients with IBD, to obtain labs with every other infusion (~3 times per year). Typically, I will obtain a CBC/d, CMP and CRP and obtain other labs like Vit D, GGT, Quantiferon Gold and drug level monitoring less frequently. I rarely check Vit B12, ESR, Folate, Amylase, and Lipase.

Related blog posts:

- My First Take: It is Hard to Save $$$ at a Rolls-Royce Dealership

- Increasing Cost/Use of Biologic Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Costs of Biologics for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Patient Assistance for Lab Testing

- The End of the Vitamin D Epidemic (VITAL Study)

Disclaimer: This blog, gutsandgrowth, assumes no responsibility for any use or operation of any method, product, instruction, concept or idea contained in the material herein or for any injury or damage to persons or property (whether products liability, negligence or otherwise) resulting from such use or operation. These blog posts are for educational purposes only. Specific dosing of medications (along with potential adverse effects) should be confirmed by prescribing physician. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, the gutsandgrowth blog cautions that independent verification should be made of diagnosis and drug dosages. The reader is solely responsible for the conduct of any suggested test or procedure. This content is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a condition.