From DDW 2015 and HealioGastro: Entyvio shows promise in pediatric patients

First study, abstract 321:

Namita Singh, MD, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in New York, … presented results of a prospective observational study in which they initiated Entyvio (vedolizumab, Takeda; 6 mg/kg, maximum 300 mg) — off label — via intravenous infusion in pediatric patients…The primary clinical outcomes was clinical remission at week 6 (PUCAI ≤ 10; PCDAI ≤ 10).

The study looked at 23 patients (15 with Crohn’s; eight with ulcerative colitis) enrolled between June 2014 and October 2014; median age of vedolizumab initiation was 14 years.

At 88%, the patients with ulcerative colitis had a higher rate of remission than those with Crohn’s who were at 40% [at week 6]. This trend sustained at week 14 and Singh said all patients with ulcerative colitis were in remission at week 14.

Week 6 and week 14 remission rates overall were 46.6% and 54.5%, respectively, and week 6 remission predicted week 14 remission (P < .05).

“Week 6 remission is associated with week 14 remission,” Singh said. “This suggests that we can determine early in therapy whether a patient will be a primary responder to therapy. If not, then perhaps we should move on to another therapy.”

“Longer duration from last anti-TNF exposure is associated with higher remission rates,” Singh said.

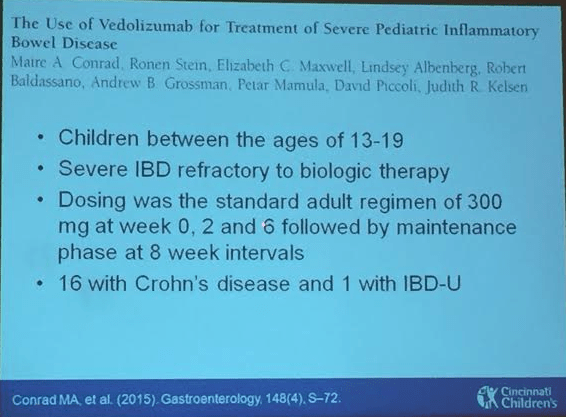

Second study, abstract 322:

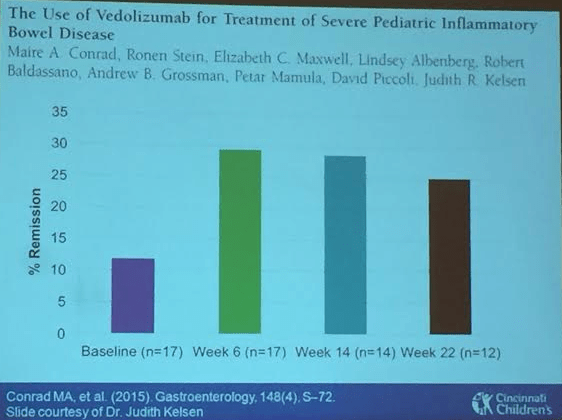

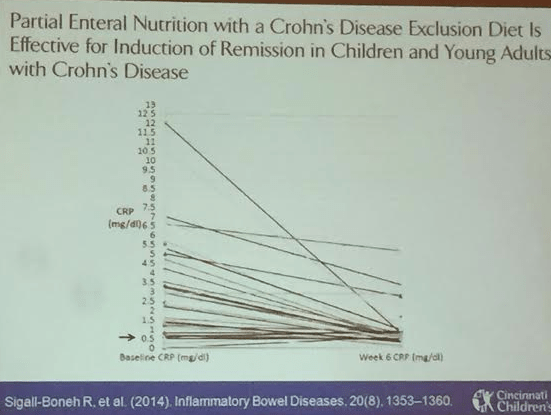

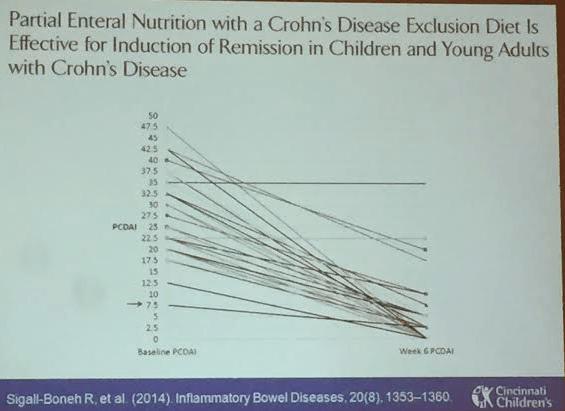

Ronen Stein, MD, from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, also presented data on vedolizumab therapy in patients with severe pediatric IBD…In this single center, prospective observational cohort study, the primary endpoint was a decrease in PCDAI/PUCAI from baseline to weeks 6, 14 and 22 and secondary endpoints were changes in albumin, hematocrit and CRP as well as remission at the same time points.

Patients received vedolizumab infusions (300 mg) at weeks 0, 2 and 6 for induction and maintenance through week 22.

The researchers included children aged 13 years to 21 years (n = 17) with IBD who weighed 40 kg or more and had a past failure on TNF-alpha inhibitor therapy. Of these patients, 15 had Crohn’s disease and two had unclassified IBD (IBD-U).

More than three-quarters started on systemic corticosteroids at baseline; more than one quarter were on immunomodulators. Seven patients had previous abdominal surgery and 59% of patients had failed more than one biologic therapy…

At each time point in question, this study saw improvement of PCDAI (P < .001 at week 6; P < .05 at week 14; P < .0001 at week 22).

“Starting at week 6, there was a significant decrease in PCDAI that was sustained for weeks 14 and 22.”

Five patients reached remission at week 6.

“There really is no pattern to tell us which patients will be in remission at week 6. They have pretty different characteristics,” Stein said.

Briefly noted:

Link: Case description/images of 9 year old with gastric Crohn’s

Related blog posts:

I love Ria’s Bluebird –the best pancakes ever!