CFD Li Wai Suen et al.Gastroenterology, Volume 170, Issue 1, 118 – 131. Early Infliximab Levels and Clearance Predict Outcomes After Infliximab Rescue in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Results From PREDICT-UC

Methods: Data, including serum and stool testing, was extracted from from 135 patients (ages 24-42) enrolled in the PREDICT-UC prospective, randomized controlled trial

Key findings:

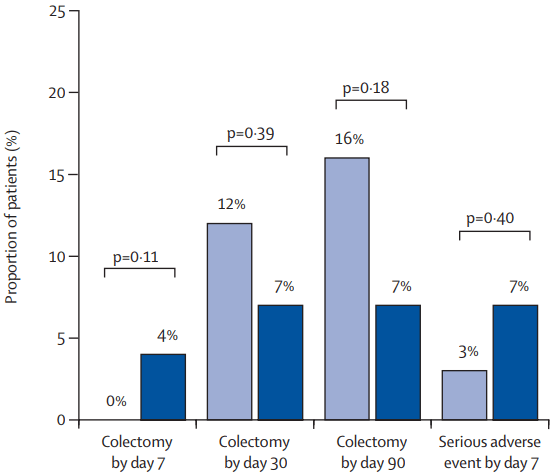

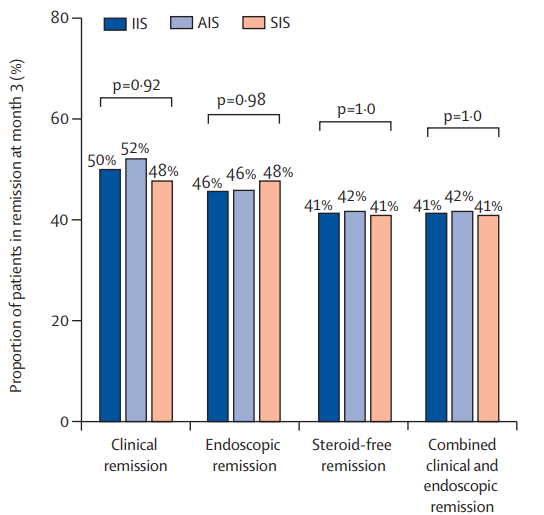

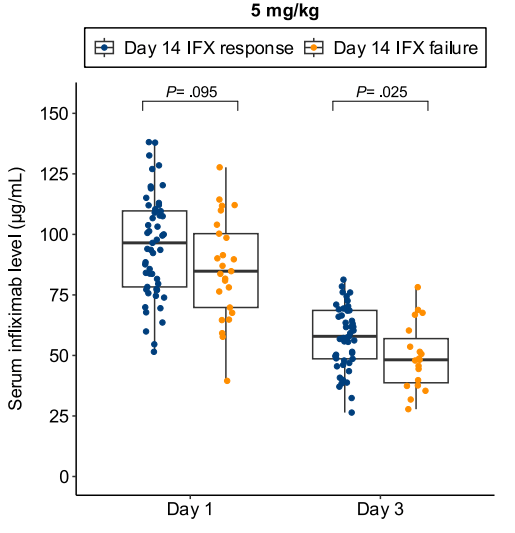

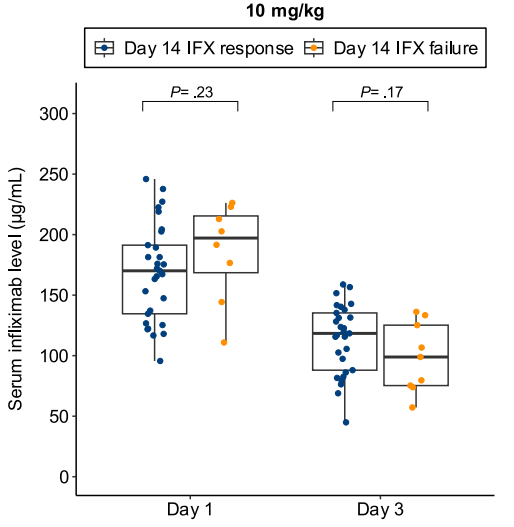

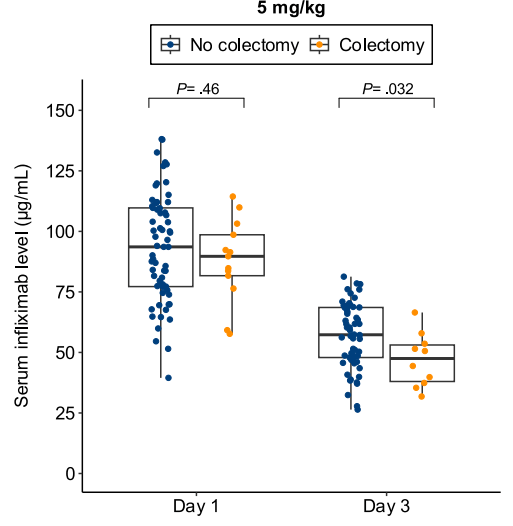

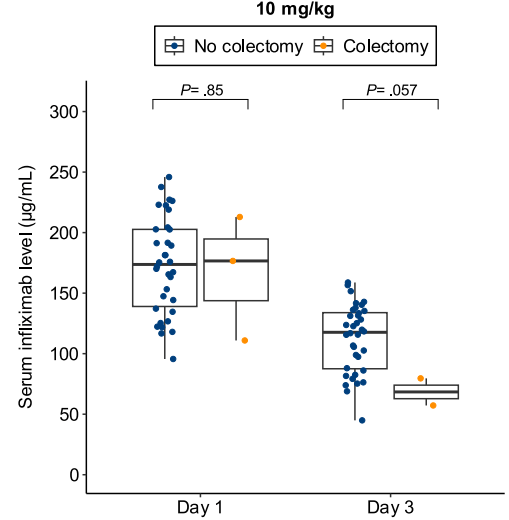

- Lower day 3 serum infliximab levels predicted infliximab failure on day 14 and colectomy by 3 months; a threshold of ≤57.9 μg/mL had 83% sensitivity, 67% specificity, 24% positive predictive value, and 97% negative predictive value for colectomy

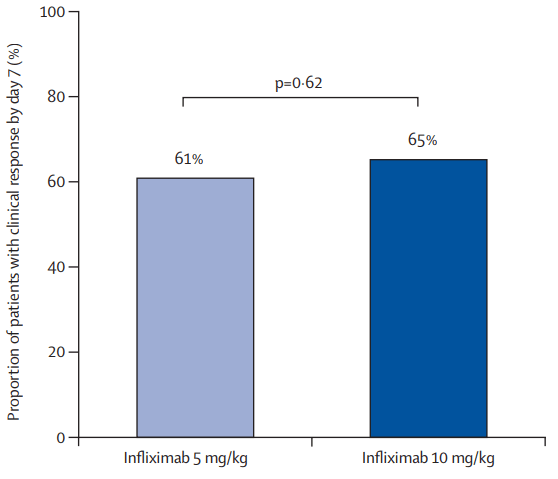

- In patients with high clearance who did not respond to the first infliximab dose, day 14 response rate was higher with a second 10 mg/kg vs 5 mg/kg dose (38% vs 11%; risk ratio, 3.43)

- Day 3 fecal infliximab levels correlated with endoscopic severity and was associated with day 7 nonresponse (P = .016)

Discussion points:

“Early infliximab levels and clearance predict outcomes in ASUC. Additionally, we are the first to demonstrate that a high early infliximab clearance can be overcome by additional dosing. These results demonstrate the potential of early infliximab TDM [therapeutic drug monitoring] to guide decision-making in ASUC and for the first time provide an evidence base for intensified infliximab dosing in clinical practice.”

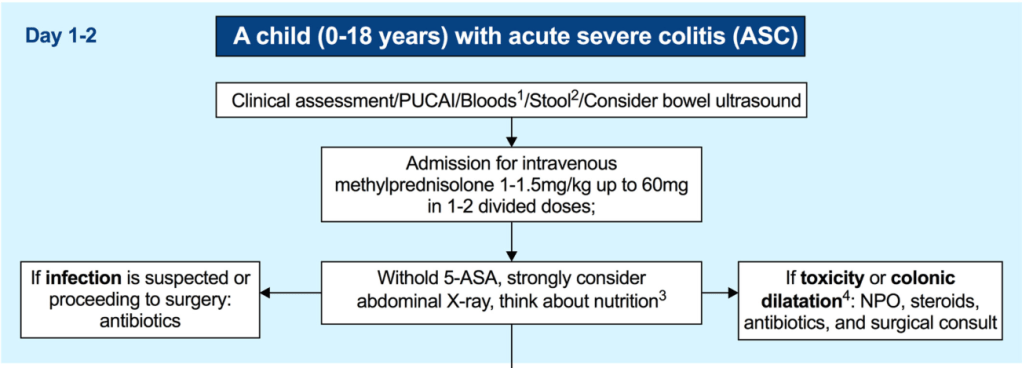

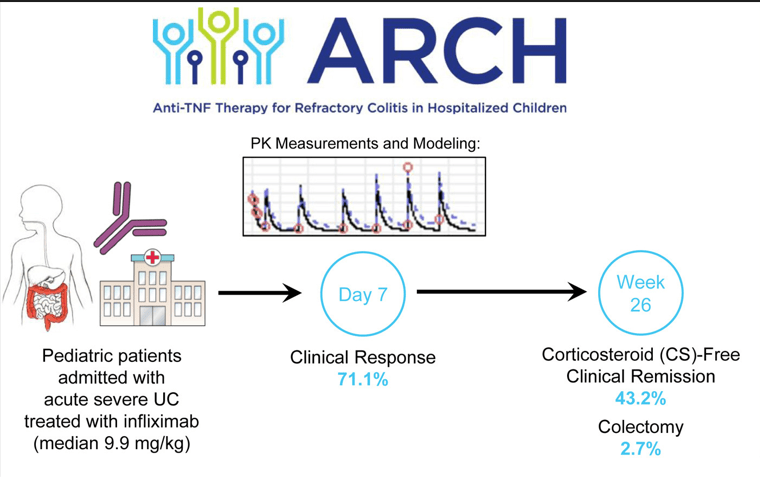

My take: While the authors suggest TDM as a potential strategy to overcome low levels, an alternative approach would be using higher dosing and more frequent dosing, especially as infliximab levels may not be quickly available. Higher dosing is particularly important in the pediatric age group where studies have shown that “standard” dosing of 5 mg/kg result in insufficient levels of infliximab in ~80%.

Related blog posts:

- Why Pediatric Patients Need Higher Dosing of Infliximab

- NASPGHAN Pediatric Position Paper for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

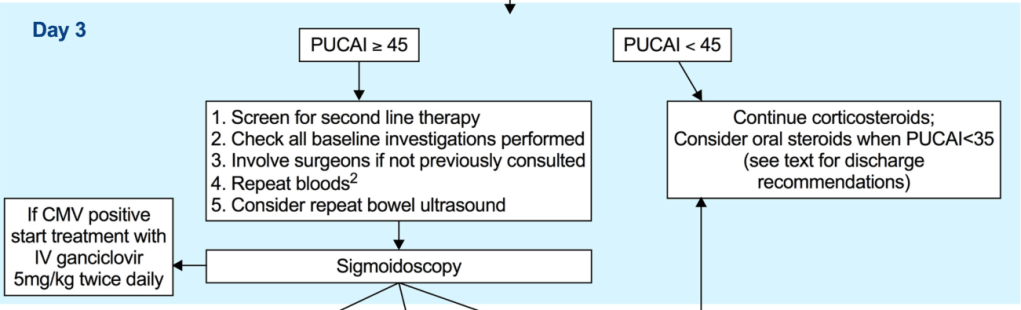

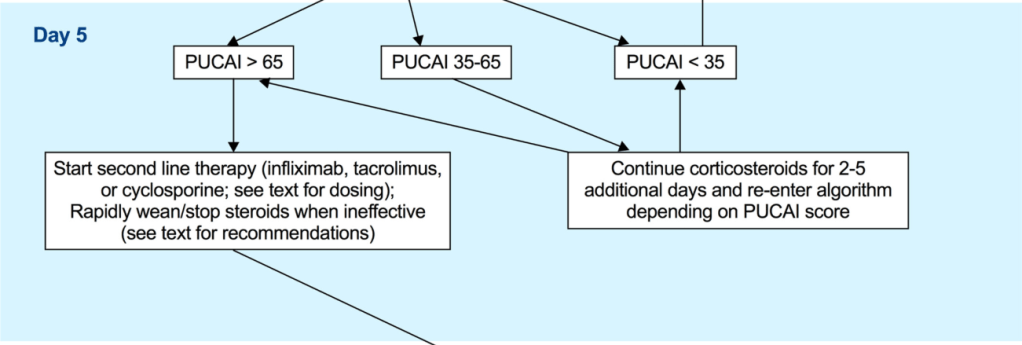

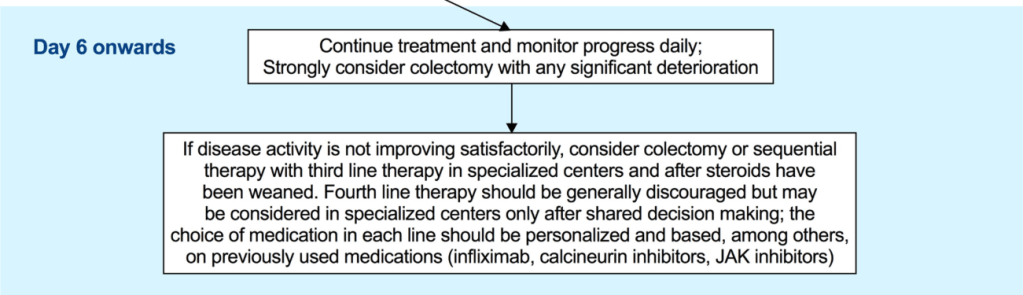

- Pediatric Guidelines for Ulcerative Colitis (Part 2: Acute Severe Colitis)

- Higher Stool Infliximab Correlates with Poor Response in Severe Ulcerative Colitis

- Comprehensive ACG Clinical Guidelines for Ulcerative Coliits (2025)