S Karjoo et al. JPGN 2025;81:485–496. Evidence-based review of the nutritional treatment of obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in children and adolescents

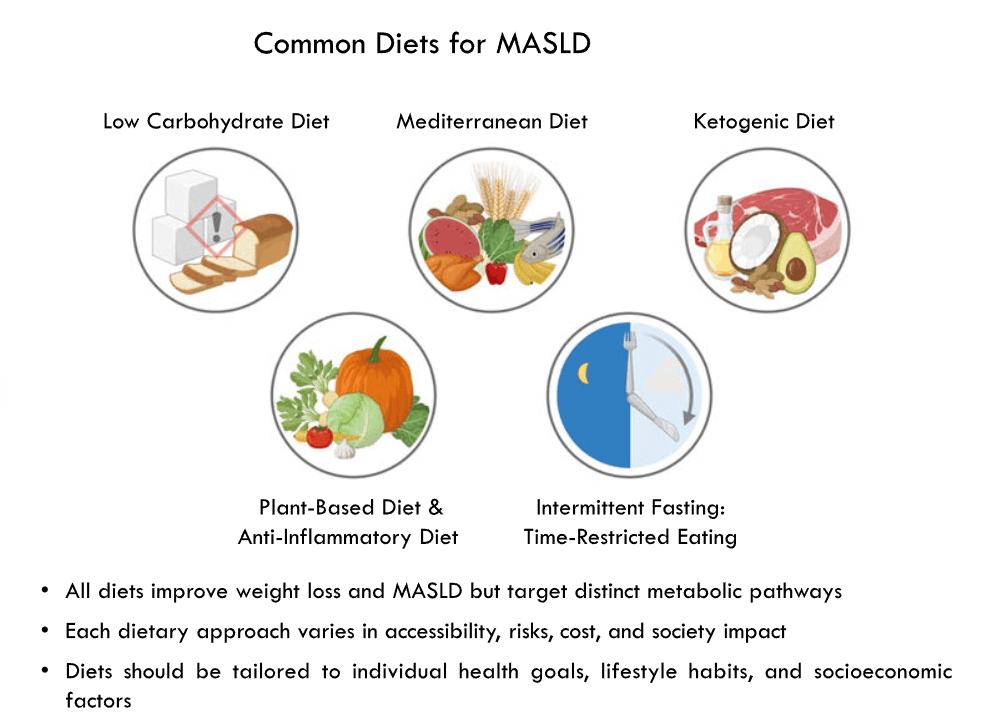

This invited commentary reviews the data for several diets that may improve weight loss and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MSALD).

Several points:

- “Extremely restricted plant‐based diets may have deficiencies of vitamin D, calcium, and vitamin B12 which are nutrients found in animal products, and can be minimized by vitamin supplementation or increasing consumption of fish, mushrooms, egg yolk, cod liver oil, salmon, herring, and sole fish. VitaminB12 supplementation is recommended in plant‐based diets because this vitamin is primarily found in animal products”

- Table 1 compares the structure of these diets and their advantages/drawbacks

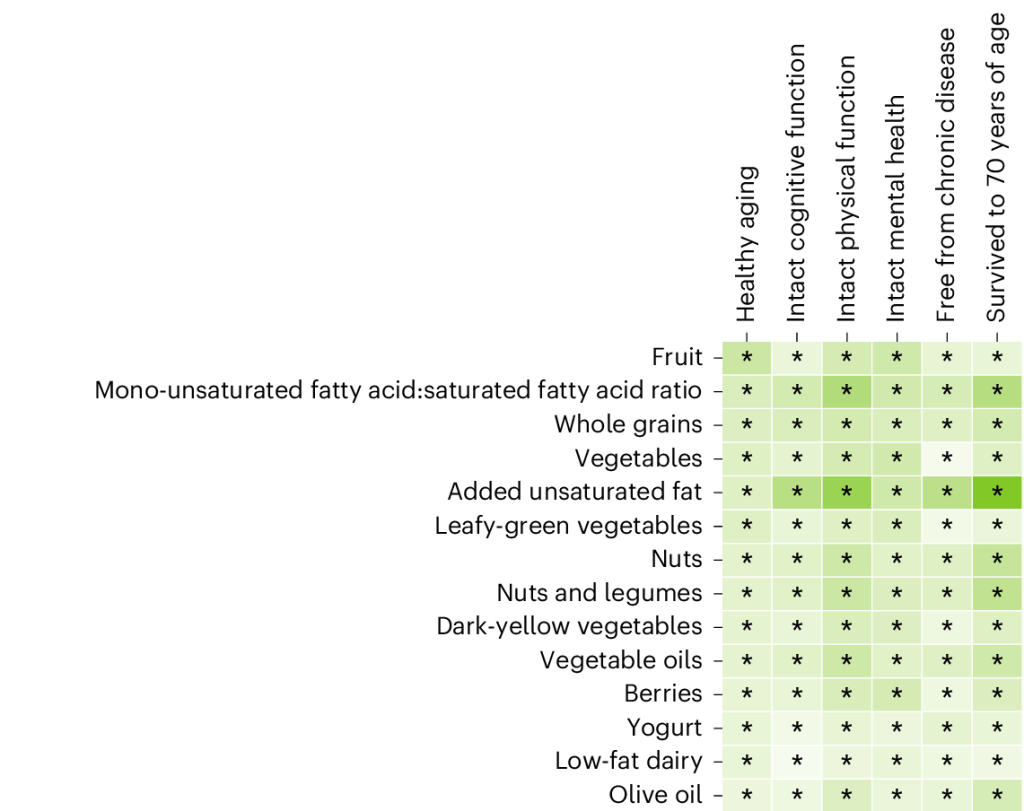

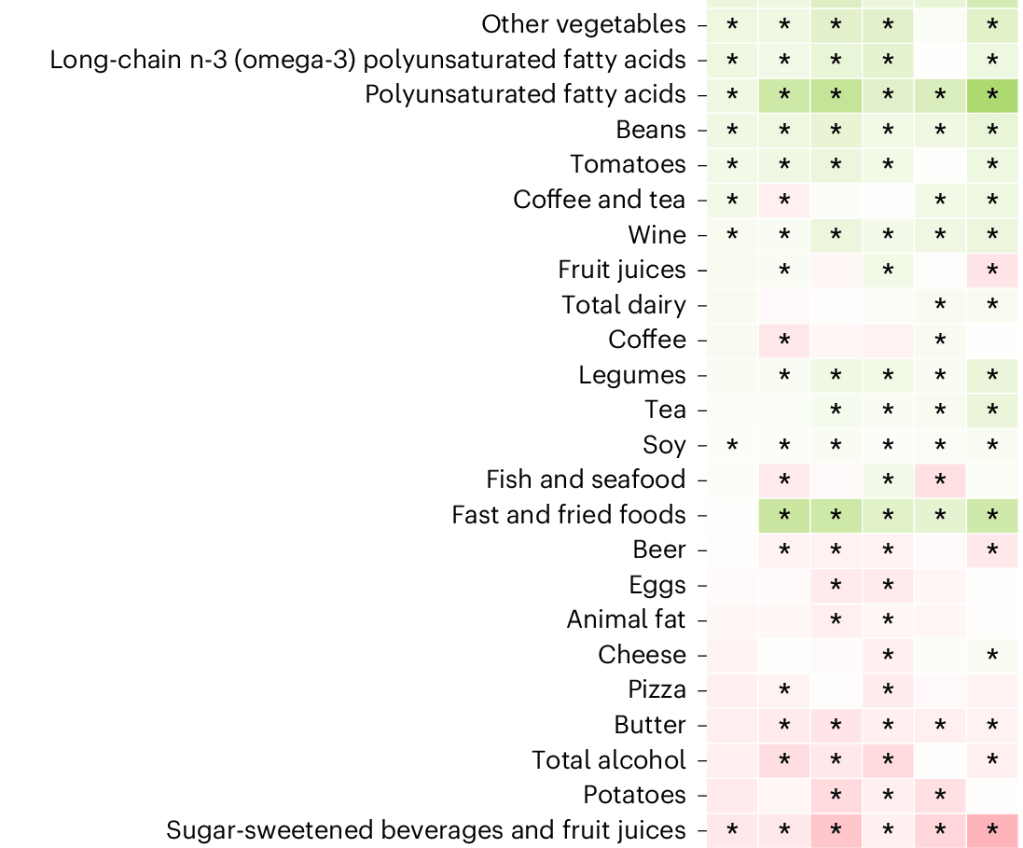

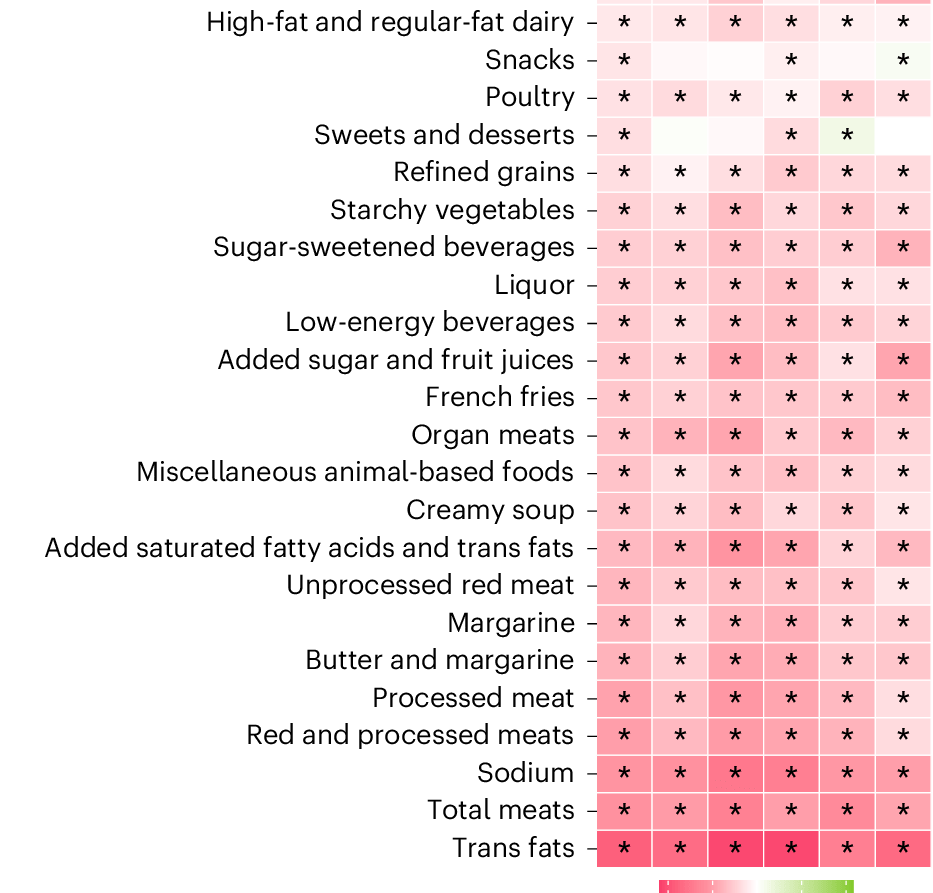

- “Low to moderate weight loss can be seen in the anti-inflammatory diet, plant-based diets, or Mediterranean diet. These diets are nutritionally complete. However, restrictive plant-based diet carries a risk of micronutrient deficiencies, which can be corrected with appropriate supplementation. These diets are effective in treating MASLD independent of weight loss due to their anti-inflammatory profile.”

- “The ketogenic diet, certain carbohydrate-restricted diets, and intermittent fasting can lead to more weight loss but carry a higher risk of malnutrition. Children on these diets must be followed by nutritionists.”

My take: Each of the diets reviewed can help MASLD and obesity. Most patients pursuing dietary therapy would benefit from working with a nutritionist.

Related news: TEVA Press release, August 28, 2025: Generic liraglutide (need for daily injections) is now available.

Related blog posts:

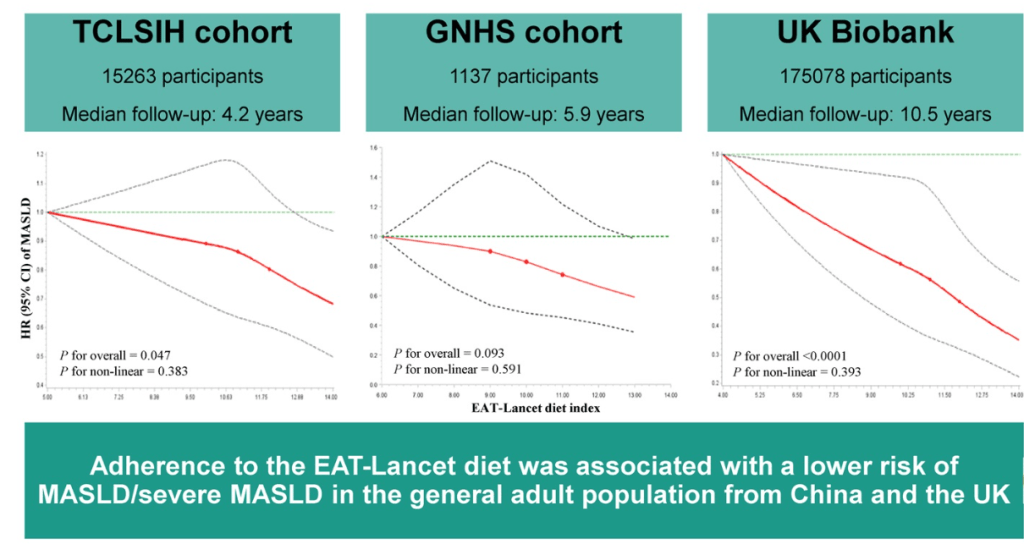

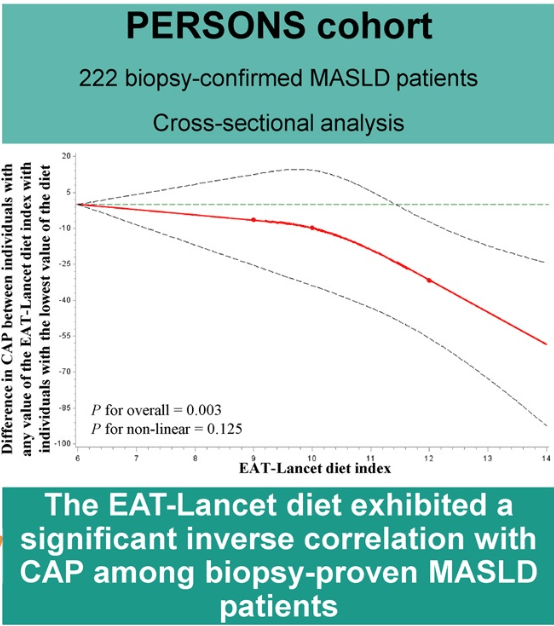

- EAT-Lancet Diet Associated with Reduced Risk of MASLD

- Pharmacological Management of Pediatric Steatotic Liver Disease

- Key Insights on MASLD from Dr. Marialena Mouzaki

- AASLD Practice Changes for Metabolic Liver Disease in 2024

- Prevalence of Steatotic Liver Disease in U.S. And Risk of Complications

- Six years later-Mediterranean diet comes out on top

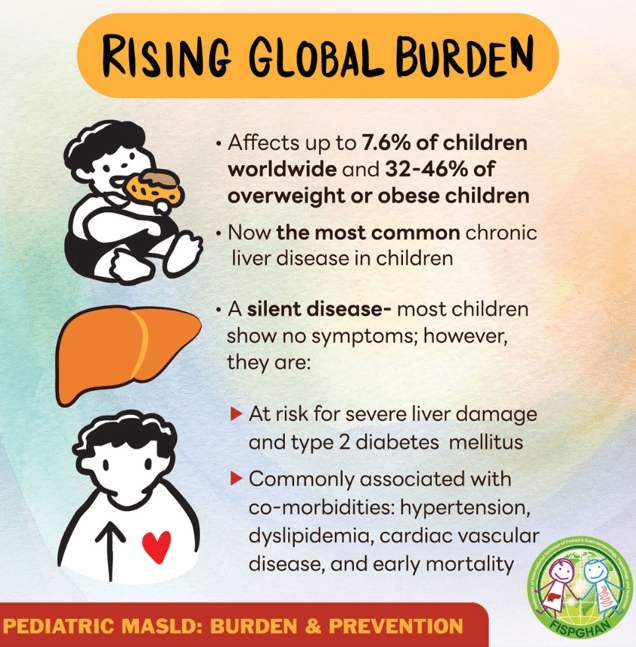

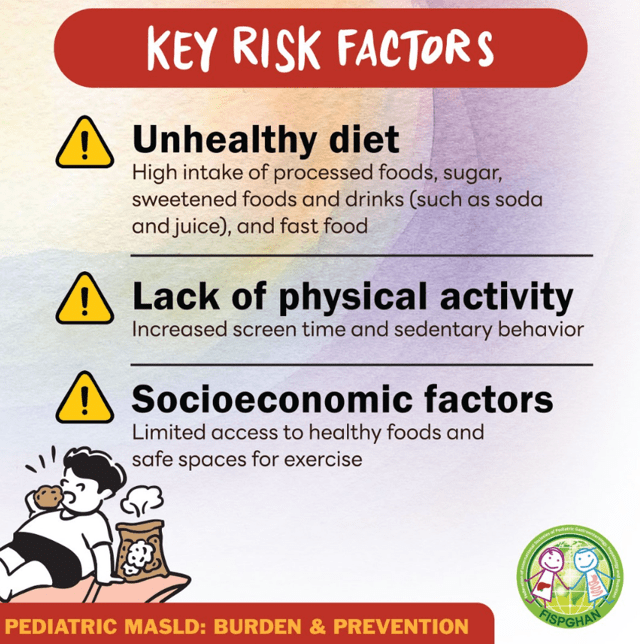

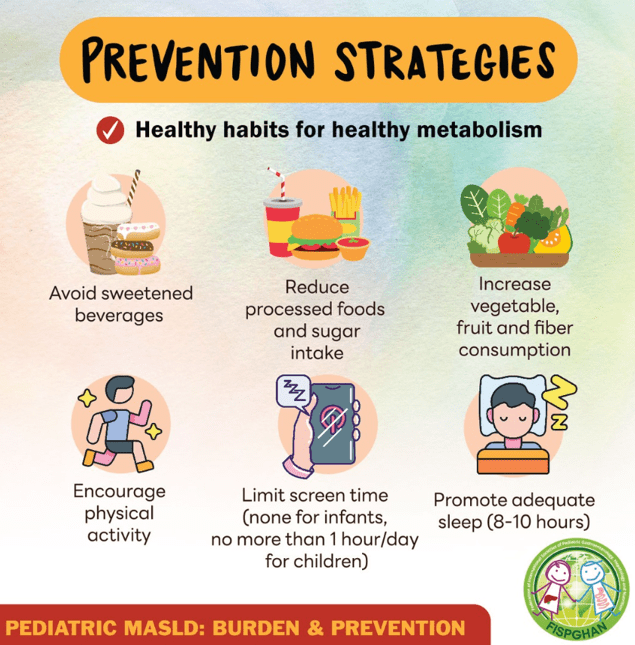

Also, related patient advice from Federation of International Societies for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (FISPGAN) –outlines risk factors and prevention tips for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD):