H Sutton, RJ Sokol, BM Kamath. Hepatology 2025; 82: 985-995. Open Access! IBAT inhibitors in pediatric cholestatic liver diseases: Transformation on the horizon?

This review article is one of many in the same issue (#4) of Hepatology.

Key points:

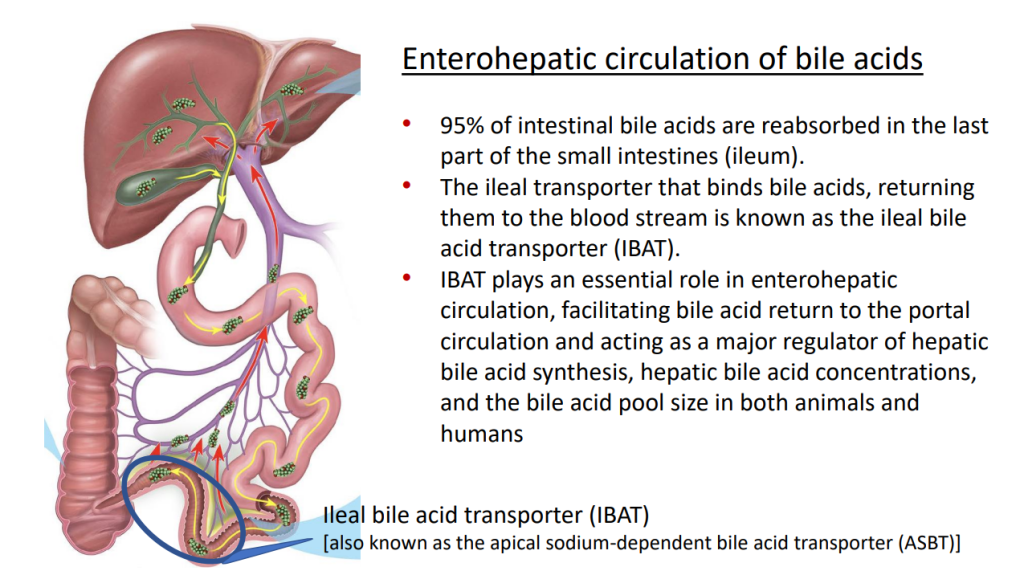

- “In the last few years, a novel class of agents, intestinal bile acid transporter (Ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT); also known as apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter [ASBT]) inhibitors, has emerged and gained approval from the FDA… the pivotal studies on which these approvals were granted were all performed in rare pediatric cholestatic diseases, namely Alagille syndrome (ALGS) and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC).3 Additional expansion of these approvals will possibly follow as there are ongoing trials of IBAT inhibitors in primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and biliary atresia.”

- “The role of bile acids in promoting hepatic injury in cholestasis is perhaps best illustrated in human infants with ABCB11 (bile salt export pump; BSEP) disease or PFIC type 2…The response to IBAT inhibition in this disease further supports the notion that retained bile acids are a key factor leading to progressive liver injury and cholestatic symptoms including pruritus, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, and growth failure.4“

- These medications may improve liver histology and not just reduce pruritic symptoms: “Using the MDR2−/− mouse cholangiopathy model, Miethke et al22 demonstrated that ASBT inhibition led to a reduction in both serum and intrahepatic bile acid concentrations by 98% and 65%, respectively. These reductions in bile acid concentrations were associated with improved liver biochemistry and a reduction in peri-portal inflammation and fibrosis on histology. The histopathologic improvements seen in these treated MDR2−/− are important to highlight, as they support the rationale of this therapeutic approach: that lowering serum bile acid (sBA) with IBAT inhibition leads to a reduction in intrahepatic bile acid accumulation and toxicity, improvements in liver inflammation and fibrosis, and ultimately improved liver disease biology.”

- Numerous clinical trials are listed in Table 1 (completed trials) and Table 2 (ongoing).

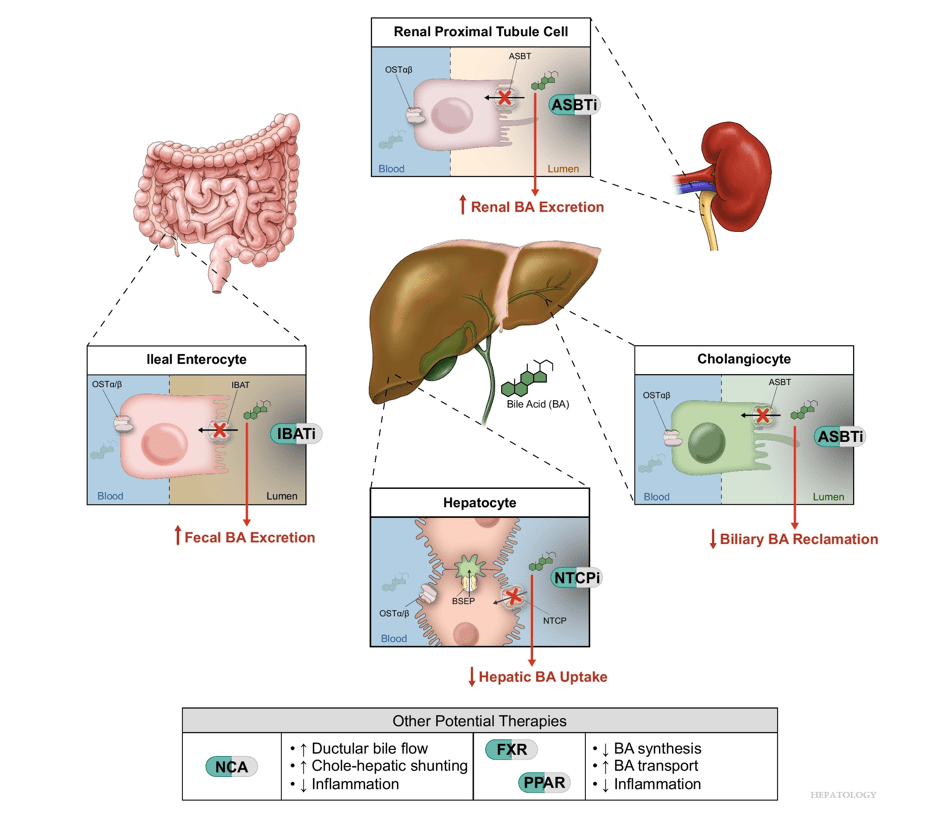

- Physiology: “Bile acids are key regulators of their own enterohepatic circulation, predominately through activation of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR)…the fecal elimination of bile acids in IBAT inhibitor–treated patients appears to far exceed the rate of synthesis of new bile acids in the liver; thus, IBAT inhibitors reduce the total bile acid pool size and the bile acid load presented to the liver.22,34,39“

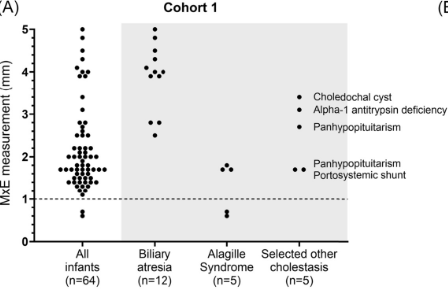

- Alagille syndrome (ALGS): Key trials are summarized including the ICONIC trial with maralixibat and the ASSERT trial with odevixibat.

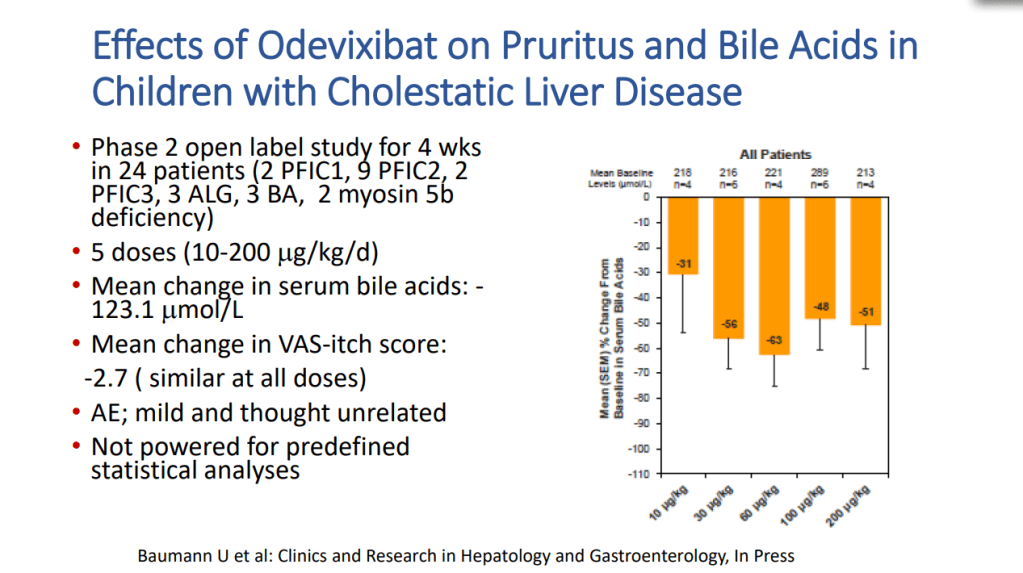

- PFIC (Type 1 and 2) Trials: Key trials are summarized including the MARCH-PFIC trial with maralixibat and the PEDFIC1 & PEDFIC 2 trialswith odevixibat.

- Safety: These medications are well-tolerated with self-limiting diarrhea and abdominal pain especially at the initiation of these medications. Liver blood test abnormalities have been noted in up to 20%. “This is an interesting finding, and the underlying etiology is unknown. Maralixibat is largely luminally restricted and so, without systemic absorption, a direct hepatotoxic effect is unlikely. It may reflect an alteration in the speciation of the bile acid pool with increasing bile acid synthesis or alterations in the gut-liver axis signaling. More importantly, it is not known if there are any clinical consequences to the increase in ALT.”

- Cost: The authors note that ursodeoxycholic acid and antihistamines are frequently used for management of pruritus. They also not that “from a cost standpoint, it seems appropriate to offer rifampin before IBAT inhibitors in the treatment of cholestatic pruritus.”

- Conclusions: “The clinical trial data are encouraging. As more physicians gain experience prescribing IBAT inhibitors, we will continue to learn how to best apply them to our patient populations. Like any new drug, there are still several unknowns. One of these unknowns is the potential for loss of efficacy…The short-term to medium-term clinical effects of IBAT inhibitors are clear, but we have not yet begun to see the long-term benefits. Whether durable reductions in oncogenic and fibrogenic bile acids reduce rates of HCC or slow the progression of (or reverse) portal hypertension remains to be seen.”

Related article: M Trauner, SJ Karpen, PA Dawson. Hepatology 2025; 82: 855-876. Open Access! Benefits and challenges to therapeutic targeting of bile acid circulation in cholestatic liver disease

“Recent advances in understanding bile acid (BA) transport in the liver… This has led to new treatments targeting BA transport and signaling. These include inhibitors of BA transport systems in the intestine and kidney (IBAT/ASBT inhibitors) and liver (NTCP inhibitors), as well as receptor agonists that modify BA synthesis and transport genes. BA analogs like norucholic acid also show promise. This review discusses the molecular and clinical basis for these therapies, particularly for cholestatic liver disorders.

My take (borrowed from Trauner et al): “We have arrived at a new era in the treatment of cholestatic disorders. This has been made possible by incorporating findings from discoveries into the molecular pathogenesis of cholestasis and adaptive processes that direct rational therapeutics to improve patients’ lives.”

Related blog posts:

- Six Year Data for IBAT Inhibitor Treatment for Alagille Syndrome

- Dr. William Balistreri: Whatever Happened to Neonatal Hepatitis (Part 2)

- Dr. William Balistreri: Whatever Happened to Neonatal Hepatitis (Part 1)

- Efficacy and Safety of Odevixibat with Alagille Syndrome (ASSERT Trial)

- GALA: Alagille Study

- Lecture: IBAT Inhibitor for Alagille Syndrome

- NASPGHAN Alagille Syndrome Webinar

- Intracranial Hypertension & Papilledema with Alagille Syndrome

- Explaining Differences in Disease Severity for Alagille Syndrome

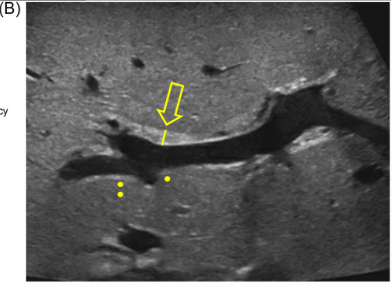

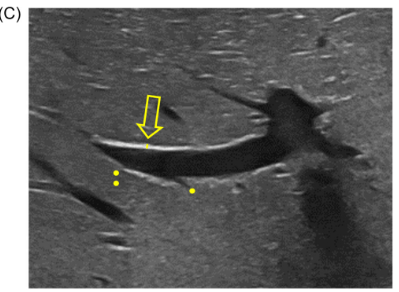

- Ultrasonography to Distinguish Biliary Atresia from Alagille Syndrome

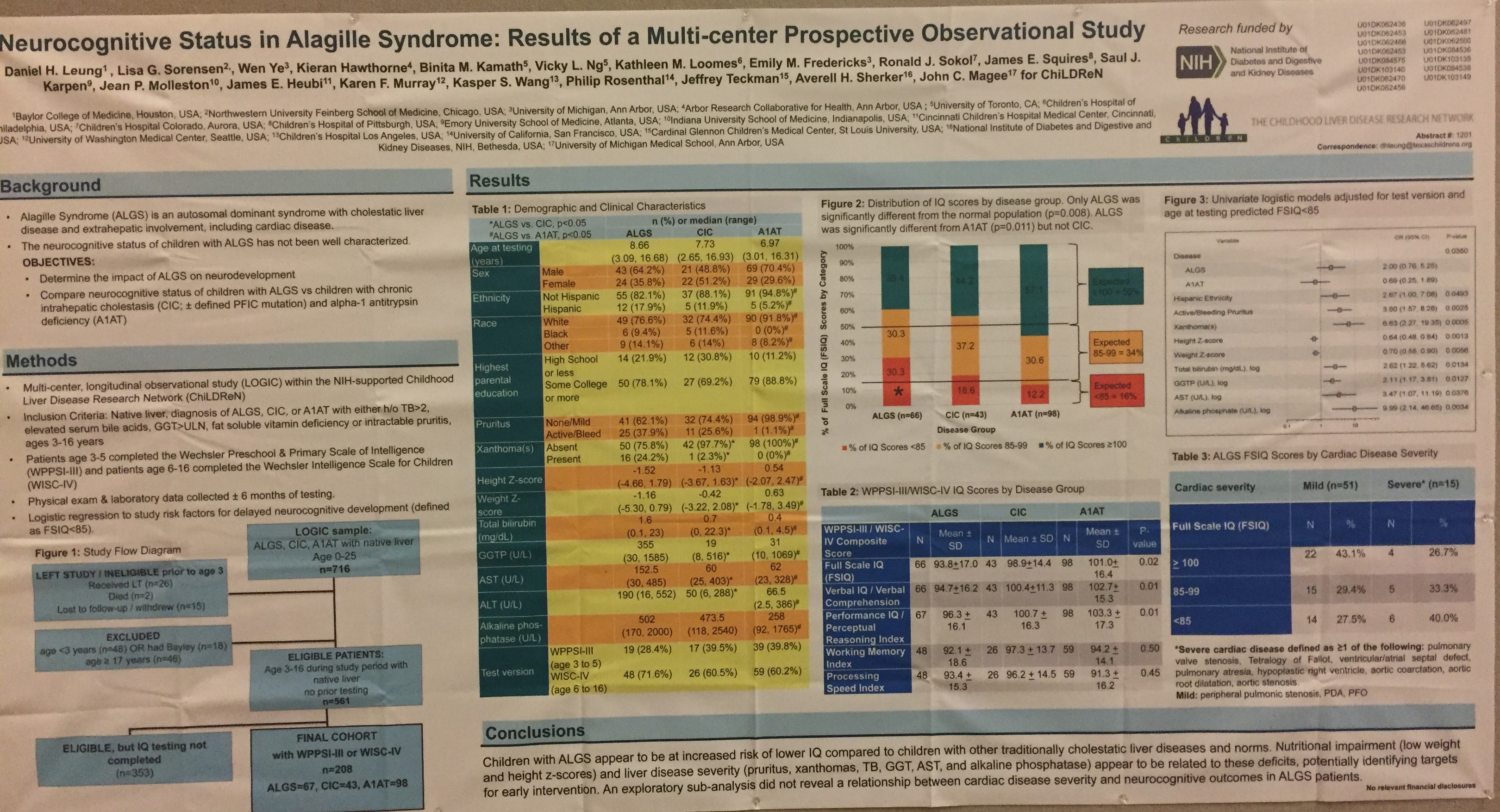

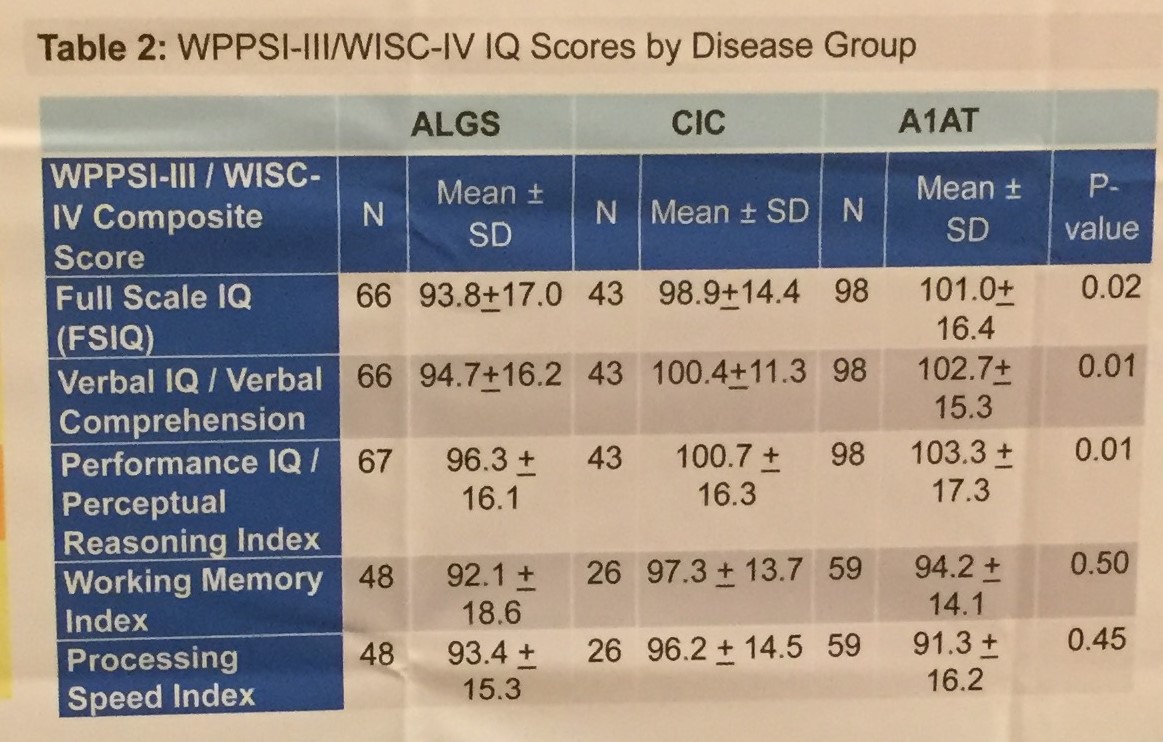

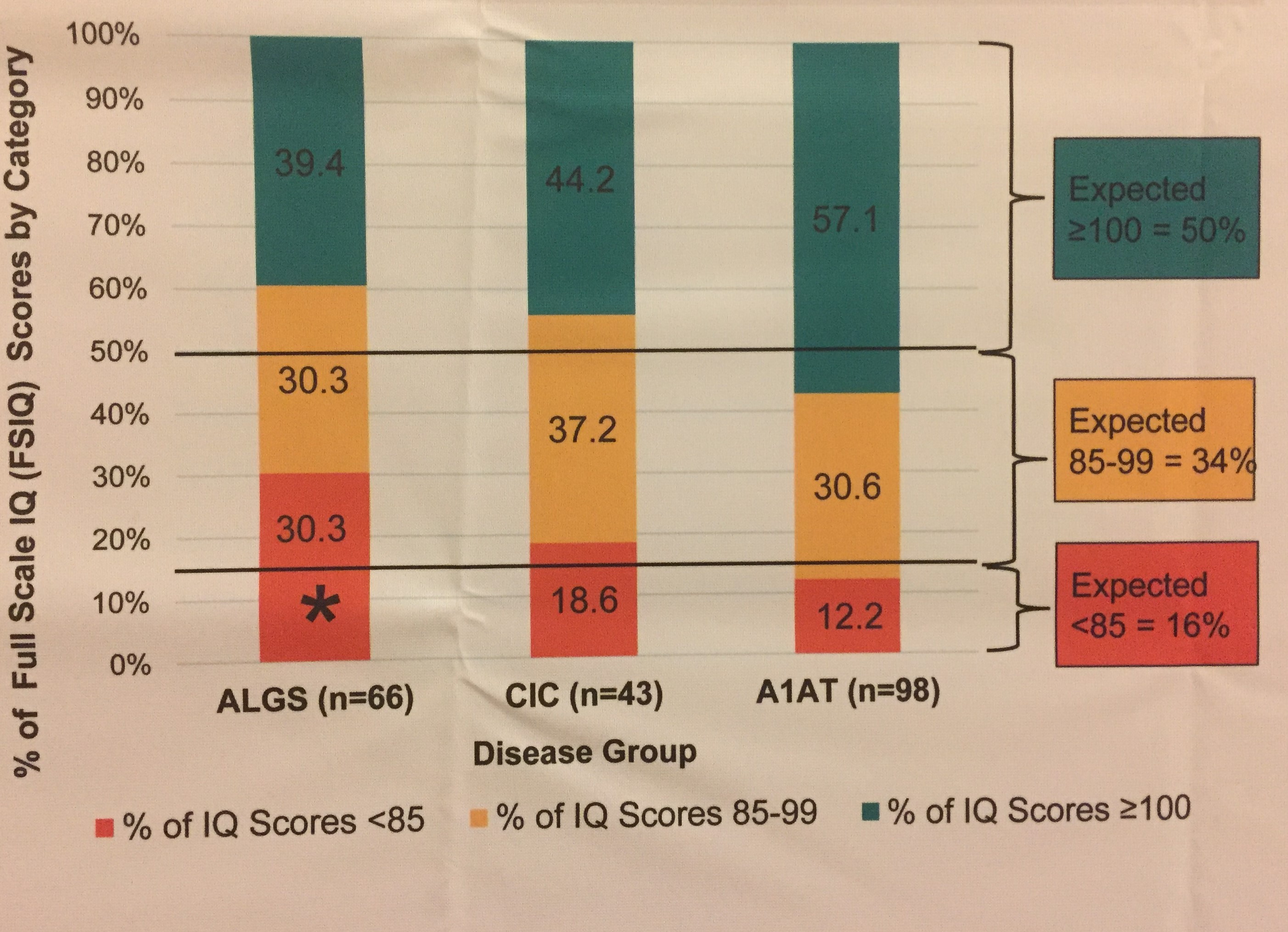

- IQ and Pediatric Chronic Liver Disease